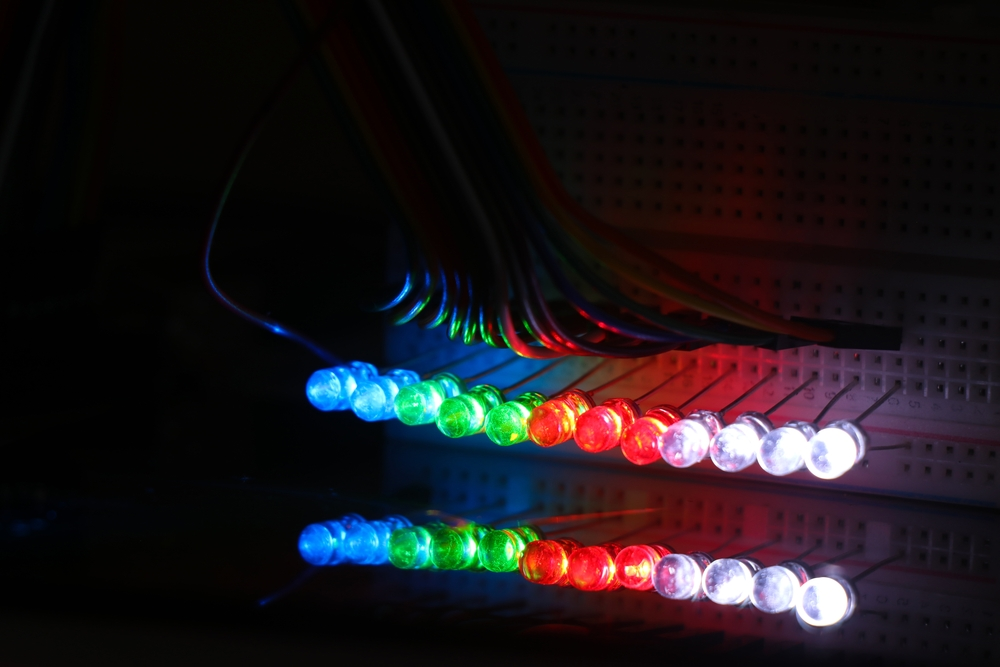

A new semiconductor with light emission spanning from violet through green to orange at room temperature

A study that challenges the long-standing problem of inefficient green emission and presents new design concepts for semiconductor materials

What the research is about

At a street intersection at night, traffic lights change from green to red. The screen of your smartphone shines brightly in response to your touch. On rooftops, solar panels quietly convert sunlight into electricity.

The materials that connect light and electricity in all these technologies are called semiconductors. Some semiconductor-based devices, such as LEDs, emit light when electricity flows through them. Others, such as solar cells, generate electricity when they receive light.

However, in the world of light-emitting semiconductors, researchers have faced a long-standing challenge. While red and blue light can be generated efficiently, green light has proven surprisingly difficult to produce with high efficiency. This unresolved problem is known as the “green gap,” and scientists have been working to overcome it for decades.

Solar cells also face their own challenges. Although high-performance materials are known, many of them are expensive or contain toxic elements, making widespread use difficult. Researchers have long sought materials that are safer, more affordable, and more versatile.

Why this matters

To address these challenges, a research team led by Professor Hidenori Hiramatsu at Science Tokyo focused on a crystal structure called the spinel structure, which has not traditionally been considered a promising candidate for optoelectronic materials.

The team fundamentally re-examined crystals with this structure, which had generally been considered “non-luminescent,” by focusing on their atomic arrangements and the behavior of electrons. As a result, they found that by selecting specific combinations of elements, even spinel-type crystals previously thought to be non-emissive can be transformed into materials that emit light efficiently. Furthermore, they demonstrated that simply substituting a small portion of the constituent elements allows the emission color to be widely tuned, not only to green but also across a broad range from violet to orange.

In addition, the researchers found that this material allows precise control over its electrical flow. They demonstrated the ability to switch between states dominated by either electrons (negative charge) or holes (positive charge), tuning the electrical conductivity by a factor of over one billion.

This means that a single new material could potentially handle one of the most essential requirements in both LEDs and solar cells: the control of electrical conduction.

What’s next

This achievement provides an important key to realizing highly efficient green LEDs, overcoming a barrier that has limited device performance for many years. Improvements in energy efficiency for lighting and displays could significantly change the technological landscape of our daily lives.

At the same time, by utilizing its ability to convert light into electricity, this material may contribute to the development of next-generation solar cells. Because it does not rely on highly toxic elements, it also holds promise for environmentally friendly device technologies.

Comment from the researcher

This research was led primarily by Assistant Professor Kota Hanzawa in our laboratory, and it represents the result of nearly five years of persistent effort by all co-authors. Even when a certain performance is considered impossible, I believe that by carefully understanding the true nature of a material and applying the right modifications, we can always discover materials that make it achievable.

(Hidenori Hiramatsu:Professor, Institute of Integrated Research, Institute of Science Tokyo)

Dive deeper

Contact

- Remarks

- Research Support Service Desk