A luminescent Switchbody! Antibodies engineered to emit light when they find antigens

A new mechanism in which an antigen releases a light-producing component held by an antibody

What the research is about

More than 100,000 different types of proteins exist in the human body, where they play essential roles in sustaining life. Some of these proteins become active only when specific molecules bind to them, triggering chemical reactions, transporting substances, or interacting with other proteins. In this sense, these proteins function like molecular switches that are turned on upon encountering certain molecules. At the molecular level, this “switching on” is accompanied by a structural change in the protein—something we cannot see with the naked eye.

By taking advantage of this property, researchers have developed a wide range of artificial “protein switches” to better understand biological processes and to explore new approaches to treating diseases. However, each protein typically binds only to a specific partner molecule, which limits the types of molecules that can turn the switch on.

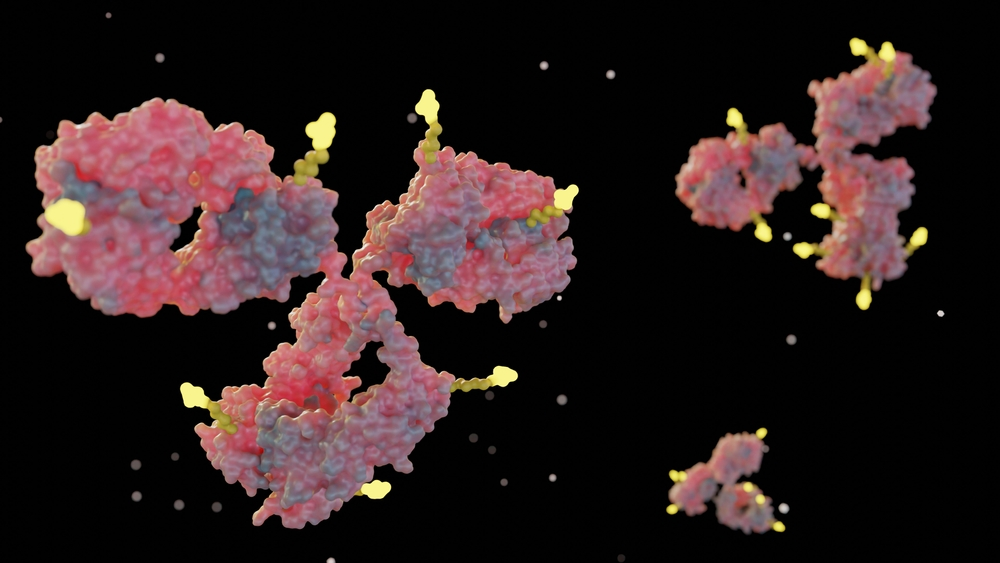

Antibodies have attracted attention as a possible solution to this problem. Antibodies are proteins that bind to antigens—molecular markers found on viruses and pathogens—and act as highly precise “molecular detectors” that recognize only their target. Because antibodies can be newly designed to match a desired molecule, using antibodies as the input part of a protein switch would allow many different molecules to activate the switch.

However, converting the information that an antibody has recognized its target into an output—such as emitting light, changing color, or producing a substance—has required complex designs and long trial-and-error processes. This difficulty has been a major obstacle to practical applications.

Why this matters

To overcome this challenge, a research team led by Associate Professor Tetsuya Kitaguchi and Assistant Professor Takanobu Yasuda at Institute of Science Tokyo (Science Tokyo) developed a novel protein switch called Switchbody, based on a “trap-and-release” mechanism. The Switchbody created in this study outputs blue light upon antigen binding.

The blue light is produced by an enzyme that can be split into two separate parts. When divided, the enzyme can no longer emit light. In the Switchbody, the antibody “traps” one of these parts. When the target antigen appears, the antibody releases the trapped part and instead binds to the antigen. The released part then combines with the other enzyme part, restoring the enzyme’s activity and emitting light.

The research team investigated this trap-and-release mechanism in detail using X-ray analysis, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)—a method for studying molecular structure and motion—and molecular simulations. These analyses revealed how the switch is turned on at the molecular level.

Because antibodies share a similar basic structure, this mechanism can be applied to different antibodies. Moreover, by changing the trapped enzyme component, Switchbody can be designed to produce outputs other than light. In this way, Switchbody can be easily customized for different purposes.

What’s next

This technology is expected to lead to new diagnostic methods that can detect disease-related molecules with high sensitivity, as well as research tools for precisely controlling cellular functions. In the future, it may also enable treatments that release drugs only where disease markers are present, potentially reducing side effects.

Comment from the researcher

In recent years, technologies for predicting protein structures and functions have advanced rapidly. By applying these technologies to the design of Switchbodies, we will be able to create proteins with functions tailored to our specific needs. This not only helps us understand what it means to be alive, but also provides clues about how life might have originated. Looking ahead, we aim to expand this research toward constructing life-like systems from the bottom up, shifting from observation to design and creation of biological functions.

(Tetsuya Kitaguchi: Associate Professor, Institute of Integrated Research, Institute of Science Tokyo)

Dive deeper

Contact

- Remarks

- Research Support Service Desk